Por Tom Spurgeon

Publicado originalmente en The Comics Reporter dot com

– – – – – – – – – –

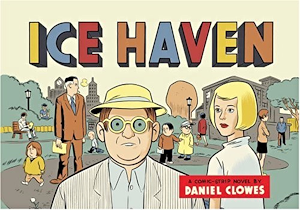

10 — “Ice Haven”, by Dan Clowes

Collection of Previously Published Material, Pantheon, 037542332X, $18.95

This reads differently than in its original comic book formatting, but only because Clowes’ work is so deeply attuned to its own presentation that moving from comic to book can’t help but make a difference. One of the two or three smartest comics to be released in the last half-decade, with dozens of cogent points about crime, community, criticism and yes, even comics; there are multiple on-ramps for discussion, from presentation right down to the visual clues provided as to the running mystery involved with the book. I think my favorite thing about the book is how it uses a random gathering of comics styles along the lines of a rack of comic books or a Sunday comics page as a community snapshot, the way that overlapping attempts at the truth can feel more trustworthy than a single, clear truth.

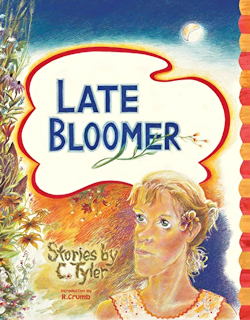

09 — “Late Bloomer”, by Carol Tyler

Collection of Previously Published Material, Fantagraphics, 1560976640, $28.95

An astonishing collection of short stories, the vast majority of which have been published hither and yon over the last 15-20 years, Late Bloomer puts Carol Tyler in the first rank of American cartoonists. These stories are alternately funny and tragic, sometimes both at the same time, but every plot point is observed with lacerating insight and every moment of catharsis is earned. Tyler is fearless. She dissects her relationships, her career mis-steps, her at-time overwhelming guilt, her feeling about pursuing art, and her skill as a mother in such a matter of fact way it’s almost stunning—there are very few cartoonists would ever depict themselves visually as ragged as Tyler make herself look, forget about going into the sordid detail of setbacks and bad decisions. With this collection, handsomely appointed and when delivered from the artist including a packet of seeds (!), Tyler also reminds the reader of her singular approach to color. It’s only when you step back from the heat of the individual comics moment that you realize the skill involved. Late Bloomer is as good as anything Fantagraphics has ever published.

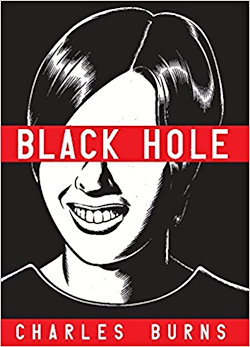

08 — “Black Hole”, by Charles Burns

Collection of Previously Published Series, Pantheon, 037542380X, $24.95

A virtuoso display of comics art, layered enough to reveal multiple insights on multiple readings and keyed into such delicate feelings about growing up and self-worth that I can’t imagine anyone getting through it without feeling a bit of its emotional weight. I’m honestly still struggling with this book; every time I reach outside the volume I see something about “AIDS metaphors” and I no longer feel like I’m being helped. There’s something about the way depicts his teen plague that seems less like he’s point out the connection between real world parallels and more like he’s the first guy to notice that something that’s always there, in everybody. It’s an odd thing to say about a horror comic, but it’s almost as if the horror elements are there to make the case that they shouldn’t be. If there were horror elements to your childhood, you’ll recognize the mindset, the way that a teenager will take the drama of the moment and fill in the blank space with dark things. The real horror of those teen years, and something I think Burns speaks to very eloquently, is that not everybody makes it out, and no one does without feeling they were made different.

07 — “Buddha Volume 6”, by Osamu Tezuka

Translated and Collection of Previously Published Material, Vertical, 1932234489, $24.95

I always get the feeling that most people have stopped reading this series, which at this point would be a shame because with the last couple of volumes the stories are increasingly flattered by the wild approach Tezuka took the material; the story of Ananda reminds me of one of the better Western myths you’d hope your schoolteacher or Sunday School designate would linger over. It’s hard to point out a more pleasurable mass of cartooning in any given year than one of these beautiful tomes, a better argument for the relative health of literary comics, or a better check against becoming too comfortable with our own comics narrative traditions.

06 — “The Complete Peanuts”, by Charles Schulz

Series of Comic Strip Collections, Fantagraphics, $28.95 a Volume

I’m not sure what to say about such a staggeringly great work entering into its prime except I can’t imagine looking forward to 25 volumes of anything else. The great Peanuts resurgence isn’t about discovery for a lot of us, or re-discovery as much as putting something in the living room that might have been in a box in the attic, the restoration of Peanuts as a central, recurring reading experience. What’s odd, then, is a lot of what I’m getting this time as I go through the books is an appreciation for the cartoonist’s accomplishment, the skill and effectiveness of these comics. Schulz was a killer gag writer, and as much as the cumulative effect you get from reading the latest book can be about sadness or frustration, digging deep into the books themselves one gets a great sense of Schulz as a skilled craftsman, assaulting the borders of what was allowed from a punchline at the same time as nearly every one of his peers settled into specific rhythms, dooming the comic strip as they went as sure as any editor that cropped and took space away.

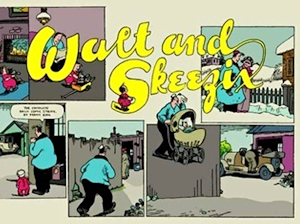

05 — “Walt and Skeezix”, by Frank King

Collection of Comic Strips, Drawn & Quarterly, 1896597645, $29.95

Not only frequently amusing, but possessed of a significant amount of what network programmers call “heart” and the rest of us merely stammer something like, “You see this guy with the kid and you feel… god, I can’t describe it.” I’m frankly surprised the strip holds up to the elaborate presentation as magnificently as it does. The other odd thing is how modern Gasoline Alley is conceptually, particularly in that it starts as a strip seeking to connect with a specific aspect of modern life—in this case, automobile culture—and then finds those elements which connect with the widest possible audience and runs with them. That’s the script straight from a modern syndicate’s sales packet. I also like the softness of the characters, their kind of doughy frailty, the way they kind of take energy into themselves rather than give it off. I hope that the remaining books are half this good.

04 — “Epileptic”, by David B.

Translated and Collected Graphic Novel Series, Pantheon, 0375423184, $27.50

Along with Jimmy Corrigan, the other giant new comics serial of the 1990s finally sees publication. David B’s great achievement is that the splendid thoughtfulness that frequently drives the art doesn’t overwhelm the book and force the narrative into a similar, over-precious design. I can’t imagine what most readers felt as the book progressed and the characters remained hard to love and the situation at hand shook itself into pieces and unsatisfying eddies of development rather than coming together both inwardly and outwardly. The lack of freaked-out gushing makes me think that many may have found the story a bit hard to enter, a bit cold. But if the graphic novel, the graphic memoir is to mean anything it has to accept those works that function as something a bit different than a paperback you buy at the airport. I found Epileptic devastating and pitch perfect.

03 — “Little Nemo in Slumberland—So Many Splendid Sundays”, by Winsor McCay

Collection of Comic Strips, Sunday Press Books, 0976888505, $135

Take a top ten all-time comics work and present it in a manner that no one thought quite possible (affordable) as of yet, and you get this book, which hopefully made designer and publisher Peter Maresca a semiwealthy man in lieu of comics’ usual reward—thousands of readers thanking him silently, over and over again, as they open the pages of their oversized volumes and get their heads ripped right off of their bodies every single time. Little Nemo in Slumberland set such a high watermark for comics design and movement I’m not sure how to compare it to anything else in any other art form. It’s as unlikely a development as a three-year-old writing symphonies, but on the grander scale of an entire form of expression. I know that film made several herculean leaps during its first couple of decades, but somehow Little Nemo feels more modern than even the most astonishing, precocious movies. It also seems appropriate to a time that moved faster and saw bigger things, a rush of sensations that must have played havoc with the senses. I wonder what kids back then dreamed after reading Little Nemo?

02 — “Krazy + Ignatz: The Second Decade 1925-1934”, by George Herriman

Collection of Comic Strips, Fantagraphics, $74

The secret to understanding Krazy Kat is that it’s really not as daunting as its reputation would have you believe. In fact, its virtues have little to do with most of what is written about the feature, all of which is true and was once important to have said, but now seems a bit unecessary. Forget the enduring love triangle. Soak in the lovely character designs. Bypass any consideration of how Herriman depicted the Southwest. Enjoy the expressive, oddball art. Forget its canny take on language as malleable self-expression, the 20th century mash of expression. Read the dialects as funny speech. Forget the pathos. Laugh at the jokes. If it didn’t work the same way all the other great strips work, if it wasn’t funny and gorgeous and possessed of characters you want to see again, all of the ways it’s unlike those strips wouldn’t be significant; they’d just be arch and sad. This decade-spanning special collection is a beautiful volume that many passed over, but I can’t imagine a comics library of more than five books where this wouldn’t be missed if absent.

01 — “The Complete Calvin and Hobbes”, by Bill Watterson

Collection of Comic Strips, Andrews McMeel, 0740748475, $150

Does the complete life of a great strip make for a better work than ten years of the greatest? For me, this week anyway, the answer is yes. A lot was made of how much people missed Calvin and Hobbes when the book was about to come out. I don’t think there’s a cultural reason there aren’t more strips like it. In most ways that count comic strips are afforded as much creative energy as they were in their heyday, and provide if not an extraordinarily lavish living, at the top it’s still a comfortable one with a very big house involved. What strips haven’t been is nearly as lucky in finding and then pushing artists that connect their facility to a profound sense of their own experiences—something you can discover deeply rooted in even the most vaudevillian of the old comics. Calvin and Hobbes was the last great comic strip of the 20th Century because of how well-crafted it was and because there’s something about a little boy of Calvin’s enormous ego that needs a stuffed animal to provide counsel and to help him get by. Plus, you know, those great dinosaurs.