“Transformaciones” es el título que le he dado a un grupo numeroso de publicaciones que he recopilado a lo largo de mi vida siendo aficionado a los comics, y que iremos compartiendo paulatinamente dentro de este blog. Algunas de ellas datan de décadas atrás y en los albores del Internet como plataforma de expresión escrita, incluyendo artículos de opinión, entrevistas y contribuciones esenciales en los años mozos de la “blogósfera”, repleta de voces con gran poder y con algo que decir acerca de este hobby que tanto nos apasiona. Todas ellas diseccionan al mundo de los comics desde diferentes aristas y matices. Algunos de ellos representan un retrovisor bastante interesante, y necesario para entender a su evolución como manifestación de las artes y plataforma multi-género. Sin mayor preámbulo, continuamos…

El laureado guionista de comics Warren Ellis ha dedicado gran parte de su carrera a analizar con profundidad a los paradigmas que le dan forma y fondo a la industria del arte secuencial. En sus artículos de opinión desmenuza sus problemas inherentes, las áreas de oportunidad a atacar y los vicios a exterminar. Sus contribuciones como un todo forman un contexto muy interesante y el cual, sin temor a equivocarnos, informa y da sentido a escritos mucho más célebres y de su autoría tales como Pop Comics y The Old Bastard Manifesto, los cuales a partir del año 2000 fueron el punto de quiebre para la introducción definitiva de la obra de autor multigénero en el mundo de los comics, y a través de formatos autocontenidos y económicamente viables.

“Tiempo Imaginario—Comics y Comunicación” es un artículo que intenta explicar (aunque con ciertas dificultades en mi opinión), que el formato del comic es en sí complicado de leer a menos que tenga un dominio (en mayor o menor medida) de una narrativa y un orden establecido que conduzca a la visión humana a través de él de una manera natural, sobre todo en composiciones de diferentes dimensiones y profundidades.

En opinión del autor, gran parte del contenido de los comics comerciales de la época carecían de dicha característica. Otras obras, por el contrario, desechan el flujo secuencial por la imagen vacía, amplia y espectacular, propia de los comics de los Noventa.

Comics de su autoría—a partir del año 2000—intentan sobremanera el controlar tanto el conteo de páneles por página como la secuencia y cantidad de frases por panel, convencido de que una narrativa moderna y accesible debe deshacerse de herramientas obsoletas en donde se satura en exposición y diálogos que reiteran lo que claramente está expresado en el arte. Explícitamente se entienden dichas líneas como una denuncia sobre el comic comercial, el cual no importando quién lo dibuje, la audiencia cautiva lo seguiría comprando tanto por inercia y completismo/coleccionismo, fomentando de esta manera la mediocridad.

Ensayos posteriores de Ellis como THE FELL FORMAT son un refinamiento más exacto y menos generalizado de esta idea, y mucho más propositivo acerca del control que el escritor debe de tener sobre la narrativa y el propio contenido de los comics.

Sin embargo, las actuales corrientes de pensamiento—sobre todo por artistas visuales, y en mi opinión bastante rebuscadas—están empezando a divorciarse de términos como “forma” o “contenido” y utilizar el concepto de “comics” como una herramienta de libre formato y estructura para crear arte pictórico (es decir, un medio para un fin), ignorando cualquier regla cognitiva establecida para interpretar el arte secuencial.

“A COMICS PAGE REQUIRES ACTUAL COGNITIVE ACTION TO DRAW NARRATIVE SENSE FROM ITS MANY ELEMENTS—WHAT SCOTT MCCLOUD CALLS “CLOSURE”—WHERE (SAY) FILM REQUIRES LITTLE MORE THAN THE EXPERIENTIAL PROCESSING DEMANDED BY EVERYDAY LIFE. I THINK AUDIOVISUAL INNOVATION LIKE THE MODERN MUSIC VIDEO HAS HAD AN EFFECT ON HOW COMICS ARE CREATED.”

—WARREN ELLIS.

Considero a “Tiempo imaginario” como el prototipo de un análisis necesario al storytelling de los comics comerciales de aquella época, libres de todo riesgo y con bajos estándares. Con el paso del tiempo y con la madurez del Internet como medio de comunicación, proliferaron en masa ensayos y reseñas tanto de autores establecidos como críticos especializados que ampliaron este discurso de una manera más concisa y didáctica.

– – – – – – – – – –

Imaginary Time — Comics and Communication

Imaginary time is the scientifically-approved “fix” that allows Stephen Hawking’s theoretical physics to operate. It’s also the glue that holds comics together.

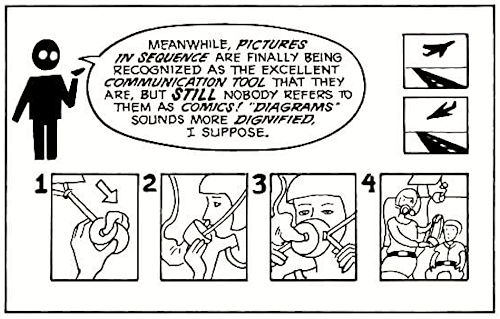

In probably this medium’s best-known work of theory, UNDERSTANDING COMICS, Scott McCloud famously demonstrated that the power of comics is in its dark matter, the invisible space between the panels. That’s why McCloud subtitled his work “The Invisible Art”; that strip of nothing between the panels is imaginary time.

He demonstrated, in that delightful way of clearly stating the bleedin’ obvious he has, that the passage of time in comics happens in the gutters (read back that last phrase. I love that. Comics happens in the gutters); that is, in the second or so of transition between one panel and the next. That blank space is where we effect “closure”. We do a little piece of logic that connects the two pictures into sequential narrative. In Panel A, the eye is open. In Panel B, the eye closes. A blink. The connections are closed, an idea is transmitted. We comprehend that a second has passed between the images. That second isn’t actually there—we just posit it in order to make sense of the panels. Or perhaps our subconscious tells us it’s there, because we know how long an eyeblink takes. That’s the essence of comics. The transmission of ideas using text and static images and the development of imaginary time.

Anyone who’s ever read a newspaper has rudimentary training in these three basic tenets, from perusal of the standard newspaper comic strip. Three or four panels laid out in a left-to-right horizontal sequence (what we call a “tier”), often in a fixed Point Of View (hereafter POV), like a pivotless camera nailed to the floor. The imaginary time involved is a matter of seconds—moment-to-moment transitions, conjuring the effect of listening in on a minute’s worth of conversation. Words, pictures, the passage of a few seconds; anyone who can construct the proffered information into a minute’s worth of narrative has the comprehension tools required to read comics, you’d think.

Christ, I wish it were as simple as that.

Well… in fact, it’s actually simpler, but bear with me for a while.

The problem I’ve intimated comes when we turn our bleary gaze onto the comic book. Nominally more complex a form than the comic strip (though God knows few large-cast superhero books handle their ensemble as adroitly as the cast of thousands that seemingly wander at will through DOONESBURY), operating in larger dimensions and pagecount, the comic book makes vastly more demand of imaginary time. For a start, a single comic book page needs to lead the reader through a much more complicated eye movement. No easy left-to-right stepping through three panels. A lot of comics demand what I call the Z eyetrack. Left to right and down to the left side and left to right again. The early releases in Paradox Press’ mystery line made wise use of this phenomenon—designed for sale in bookstores and other non-comics-specialty outlets, they played to novice comics readers by adopting a two-tier page averagely featuring four equal-sized panels, to produce a very simple Z-track. If you’re a first-time comics reader in 1997 and you get a simple Z-track comic page, though, you’re lucky. Exploded layouts and a hunt for the Big Cool Picture may give you a page that you simply cannot decipher without years of practise on similar works. The Z-track simply won’t be there. There may be no guttering. The POV will fly around like a bat on methedrine.

Most comics are simply unreadable to people who didn’t learn the requisite, highly specific skills in childhood. It’s kind of like not learning to drive until you’re past thirty—you can learn to do it, but it’s a damned sight harder than it would’ve been if you’d learned at twenty, and takes a hell of a lot more time.

The comicbook has become an inbred beast, and, as much as in subject matter, it is this that prevents comics from attaining a wider audience.

Warren Ellis

August 1997