“End It All. 2011: the best.”

Por Matt Séneca

Publicado originalmente en deathtotheuniverse dot blogspot dot com el 30 de diciembre de 2011.

– – – – – – – – – –

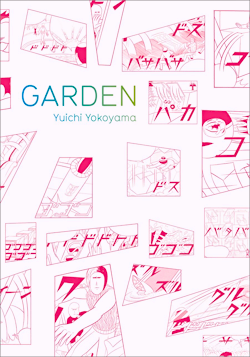

1 and 2. “Color Engineering” and “Garden”, by Yuichi Yokoyama.

Picturebox/Nanzuka Underground.

I’ve harbored the opinion that Yuichi Yokoyama was making the best comics of anyone working for years, but with the dizzying one-two punch of these books, he stated it in blazing day-glo letters for all to see. Garden was “lit comics” introduced to hardline experimental literature, a near-endless journey through human history and technology that ends in apocalypse and a hint of rebirth. That hint is ravishingly elaborated upon in Color Engineering, which may prove to be the best and final word in art-comix; a completely overpowering visual tour de force that strips the mechanism of comics storytelling back to its most basic elements before reconsidering them and giving them a polish for this new century. Yokoyama’s output in 2011 is best described as a two-part textbook, a map of where it’s possible to go—not just next year or next decade, but next epoch. Like all the truly great stuff, it’s better seen than described.

3. AFFECTED, by Matt Seneca.

Self-published online.

Whatever, I liked my comic better than all the other ones this year. If I didn’t I wouldn’t make it! It’s mostly because AFFECTED is (obviously) the exact type of content I want to see getting put out there, but there are also things I know I’m doing (because I’m the one doing them) that I wish I saw a little more of on the new racks. A cursory reading of the past decade’s aesthetically satisfying American comics gives little to no indication that we live in a nation at war, or that we’re experiencing a very real shift in the way we live our lives, or that this thing the internet exists. I also think one of the most valuable things happening in comics right now is cartoonists’ folding of the pure-visual punch of last decade’s art-comix into more considered literary structures, and the way young cartoonists are beginning to interact more directly with the medium’s history on the page—as critics and commentators rather than just followers. It’s up to you to decide whether I’m succeeding or failing, but I’m having more fun doing my best to achieve these things than I am reading any comics.

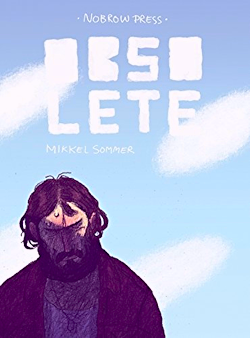

4. Obsolete, by Mikkel Sommer.

Nobrow.

If you’re looking for a perfect comic, look no further. Danish artist Mikkel Sommer’s slow-burn crime thriller Obsolete is a stone masterpiece from start to finish, not a panel wasted, not a ropy, scratched line out of place. Beautifully printed, told mostly without words, brutally short and to the point, shocking and touching in the same gasped breath, it’s almost frightening in its economy. Single gestures tell of years’ experience, scribbled landscapes cough up their fractious histories, and characters flower into vivid life with a glance or a plea. Though Sommer’s Frank Quitely-meets-Gipi art and ice-cold sense of pacing and plot are astounding, what’s most impressive about Obsolete is its tone, which throws the nervy futurism of Scandinavian crime literature over a heartbreaking Mideast War fallout narrative. It’s a lightning bolt from a clear blue sky to see something this accomplished—we’re talking Eisner-on-Spirit, Ditko-on-Question levels of bluntly stated, transcendent genre comics—from such a complete unknown. After such a formidable display, Sommer deserves our full attention. To my great shame, I didn’t review this one yet, but rest assured I will soon. In the meantime you should definitely buy the thing.

5. 2001, by Blaise Larmee.

Self-published online.

In a year of formalist comics, Blaise Larmee’s gorgeous, ephemeral 2001 managed to be both the prettiest and the most relevant. It’s a stunning thing to look at, filling every computer screen it’s spread onto with a minimal, hauntingly evocative black and white world that moves with the verve and decisiveness of youth. Larmee’s drawing has developed to a point where it can stand comparison with just about anyone else making comics at the moment, and each panel of 2001 is a treasure, more than enough to keep frozen on the screen and simply stare at. But what makes the comic so exciting is how relentlessly it pushes the reader forward, whisking the eye down and down until the experience of reading it comes just about as close to animation as still images can get. Larmee has found a new acme for webcomics, something that truly can’t be replicated on the printed page, and the 2001 site is its home environment, a place not a little bewildering in its beauty, one it seems impossible to get tired of visiting.

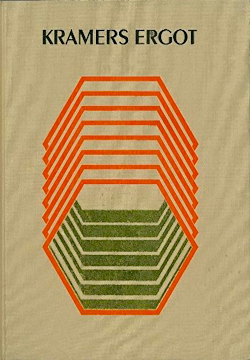

6. Kramers Ergot 8, edited by Sammy Harkham.

Picturebox.

The joyous explosions of color and noise and brilliant ideas that were Kramers 4 through 7 are probably the best printed summations of the bull market that comics experienced last decade, comics conceptualized as a (if not the) vital, modern art form with all the potential in the world. It was a creative flowering on a level that’s only been seen in comics a few times before. But every wave crashes to the shore eventually, and this new, quieter, more focused Kramers brings the comedown with a laser-beam focus. Rigid, complex story structures bracket in the visionary drawings, the small size of the book pens everything in a little tighter, and the ideas on every page seem to broil at finger-burning heat rather than bursting outward. It’s angry comics for apocalyptic times, but beneath the book’s dour pessimism (itself a highly engaging virtue) is a picture of a new world for comics, one that has perhaps reined in the excesses of the utopian vision Kramers previously put forth, but one more realistic and workable for that. And all conceptualizing aside, it’s got knockout stories from an all-star list of the best cartoonists going, including career highs from CF, Dash Shaw, and Johnny Ryan.

7. Daredevil, by Paolo Rivera, Marcos Martin, and Mark Waid.

Marvel “Fuck Marvel Comics” Comics.

Given the current state of mainstream comics, it looks pretty damn impressive when something that doesn’t allow itself to be aesthetically compromised by its milieu in any way comes along. Daredevil is just that, a superhero book that wants to be a superhero book and does so beautifully. It’s a shame that the most noticeable aspect of this series is its lack of crossover marketing hype, inappropriate attempts at “maturity”, knee-slapping editorial gaffes, et cetera, but c’est la guerre: that leaves all the more room to marvel at how well Mark Waid can layer vicious fighting and deft character acting and seamless incremental plotting into page after page of beautiful (and beautifully produced) drawing by Rivera and Martin. It’s craftsmanship, not art, to be sure, but this is work for hire that its creators deserve to be very proud of, perfectly pitched as the kind of high-octane escapism the marketing department needs it to be, but also a virtuoso-level workout for the fundamentals of action comics. They don’t all have to change the world or even the medium, but it would be quite something if they could all be this beautiful and fun to read.

Honorable mention.

“Love & Rockets New Stories #4”, by Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez AND “Ganges #4”, by Kevin Huizenga. Fantagraphics (both).

Both of these comics are completely amazing on every level, and are probably better than many of the ones on the list. But they’re also both ongoing series that have spanned many years of greatness at this point, rather than anything that belongs to 2011 exclusively. They’re not listed, but they’re on the list. Read them.